The BRCC Magnolia librarians would like to remind you about the upcoming annual book sale. The annual book sale always has some great finds! Paper back books are $1.00 and hard back books are $2.00-$3.00. So stop by the week after LCTCS and see what you can pick up.

Reprinted from Inside Higher Ed

Inside Higher Ed. (2016, April 4) A Larger Role for Libraries Retrieved April 4, 2016

https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2016/04/04/study-explores-faculty-views-scholarly-communication-and-information-use

A Larger Role for Libraries

Study explores faculty members' views on scholarly communication, the use of information and the state of academic libraries and their concerns about students' research skills.

April 4, 2016

By

Faculty members are showing increasing interest in supporting students and improving their learning outcomes, and say the library can play an important role in that work, a new study found.

Ithaka S+R’s latest national faculty survey, released this morning, shows two storylines in higher education intersecting. The results suggest the pressure on colleges to improve retention and completion rates and prepare students for life after college appears to be influencing faculty members, who are more concerned than ever that undergraduates don’t know how to locate and evaluate scholarly information.

At the same time, many faculty members view university libraries -- which are engaged in a process of reinventing themselves and rethinking their services -- as an increasingly important source not only of undergraduate support but also as an archive, a buyer, a gateway to research and more.

“We have a number of findings that show faculty members are paying more attention to students' skills and that they’re looking at the library as a partner,” said Roger C. Schonfeld, director of Ithaka S+R's libraries and scholarly communication program, who co-authored the report. “It suggests real opportunities for universities that wouldn’t necessarily be possible if it was just an administrative initiative rather than a set of perception changes.”

Ithaka S+R, a nonprofit consulting and research company, has conducted the survey -- a wide-ranging exploration of how faculty members feel about information usage and scholarly communication -- every three years since 2000. This year’s edition includes responses from 9,203 faculty members representing all arts and sciences and most professional fields at four-year colleges and universities in the U.S., collected last fall.

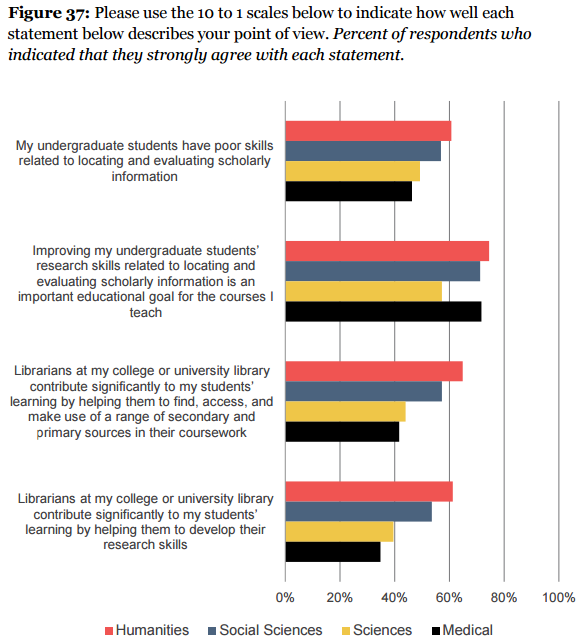

In an interview, Schonfeld said faculty members’ thoughts on their own students’ research skills are one of the most interesting developments since the 2012 survey. More than half of respondents (54 percent) described those skills as poor, up from 47 percent in 2012. Faculty members in the humanities were particularly critical, with about six in 10 respondents saying their students struggle.

Most faculty members -- about two-thirds of respondents -- said they see improving undergraduate research skills as an important goal for the courses they teach, but they are not alone in that pursuit. About half of faculty members now say librarians contribute significantly toward students being able to discover and use primary sources in their course work -- “substantial increases” from the 2012 survey.

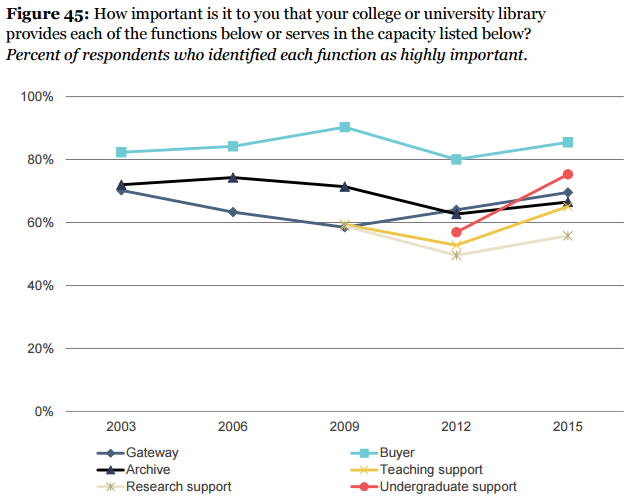

The increase in the number of faculty who see libraries as a support service for students can be seen in the qualities instructors value in their libraries. Traditionally, faculty members have rated services related to research -- acquiring new journals and monographs, serving as a starting point for research and archiving information -- as the most important aspects of a library. Those functions are still important, but this year’s respondents rated undergraduate support as the second most important service the libraries provide (behind acquisitions).

In fact, respondents in 2015 rated everything libraries do as more important than they did in 2012. The undergraduate support function saw the largest increase, from less than 60 percent in 2012 to about 75 percent in 2015.

Schonfeld pointed out that there are obviously differences between individual colleges and how their libraries are viewed by faculty, but over all, “Libraries writ large can take that as a sign of success,” he said.

Other notable findings include:

More than half (52 percent) of faculty members said they shape their research and pick their publication outlets based on what they think will work in their favor in tenure and promotion decisions. That is particular true among female respondents (59 percent) compared to male respondents (47 percent) and faculty members in the social sciences (57 percent).

“We know that there are issues around equity, and not just on a male-female basis in higher education,” Schonfeld said. “This is a good example of evidence that we have not solved these problems.”

On a related note, faculty members said some research methods are more important than others. More than half of respondents rated analysis of new quantitative (59 percent) and qualitative data (53 percent) as the most important research activities, while analyzing text, mapping data, using simulations or writing code ranked toward the bottom of the list with less than 20 percent.

Interest in all-digital scholarly monographs remains flat, even as more faculty members grow comfortable with the idea of an all-digital journal collection. About 75 percent of faculty members said they would be fine if their library stopped subscribing to a print version of a journal but continued offering it electronically. A growing number of faculty members are even warming to the idea that libraries should discard their entire print collections.

That does not apply to print monographs, however. Less than 20 percent of faculty members said they see ebooks catching on in the next five years to the point where print books will be superfluous. Print, respondents said, is easier to read cover to cover, in-depth and skim, while ebooks provide a better way to search and explore references.

“As I look at that finding, it suggests that some of the enthusiasm that faculty members had a few years ago for the potential of digital books … hasn’t been realized,” Schonfeld said.

Faculty members believe they themselves are best suited to preserve research. More than 80 percent of respondents said they preserve, organize and manage their own data, while less than 10 percent said they rely on libraries to do so. Once a project has reached its end, a majority of respondents (about two-thirds) still said they take responsibility for preserving it, most of them using freely available software. Only about 10 percent said libraries and publishers assume preservation responsibilities.

“There are some real risks here,” Schonfeld said. “There’s a preference for solutions that are seen as self-reliant.”

Dedicated scholarly databases are losing influence as a starting point for research as library websites and general search engines capture more of the market. In every previous edition of the survey, a plurality of respondents have said they start the research process by visiting a database such as JSTOR. This year, slightly more faculty members (about one-third of respondent) said they start on a general-purpose search engine such as Google.

The results also contain encouraging news for libraries, which have over the last several years invested millions of dollars in discovery services. About one-quarter of faculty members said they start their research on the library’s website, a jump from about 20 percent in 2012.

“The flux there is really interesting, and it’s important,” Schonfeld said. “It’s really powerful to see the mind share of faculty members shift away from publishers or other kinds of specific electronic resources and toward these newly developed library discovery services and general web search.”

|

| Reference Librarian, Kathy Seidel assisting students from the English 101 pilot program. |

|

| Technical Services Librarian, Laddawan Kongchum leading a bibliographic instruction session in computer science. |

Your BRCC Magnolia Librarians continue to work making research a valuable and tangible resource that students can use. This helps with retention and encourages student learning and inquiry. There are many ways to involve the library with the courses you teach. Contact your liaison librarian, call the reference desk (216-8555), or email (librarian@mybrcc.edu) to get more information. If you are uncertain who your library liaison is, the list is linked here: http://guides.mybrcc.edu/lib-liaisons.

There are many opportunities to gain from your library, some of which might be somewhat unexpected. This centerpiece was created in your BRCC Magnolia Library.

|

| Book themed centerpiece for LLA |

The annual Louisiana Library Association (LLA) conference was held last month here in Baton Rouge. Dean Joanie Chavis and Associate Dean Jacqueline Jones were heavily involved in the planning of this event, and featured these centerpieces in the grand ballroom of the conference.

|

| Centerpiece created in your BRCC Magnolia Library on display at the annual LLA conference. |

Graphic Design student Joshua Johnson, one of the library student workers, helped to design and create the centerpieces. Through this experience, he had the opportunity to showcase his design skills and gain real-world design experience.

|

| Library Student Worker Joshua Johnson working on a centerpiece. |

|

| Johnson adding the final touches to his centerpiece. |

The centerpieces were a huge hit at the conference with many librarians from across the state commenting on their uniqueness. All of the centerpieces were sold to benefit the state library association. Demand for them was high, and we are still getting inquires about how they could be purchased even though there aren't any left. Congratulations to Joshua Johnson for creating a successful and appealing design!

Continuing the creative thread, Reference Librarian Peter Klubek presented a group project at the Art Librarian Society of North America (ARLIS/NA) annual conference in Seattle, Washington. Klubek lead an pop-up postcard maker space at the conference that attracted librarians from all over the country.

|

| Postcard maker space at the ARLIS/NA conference. |

The maker space offered conference attendees the opportunity to create and mail their own unique handmade postcards directly from the conference. It also opened a dialog between participants about introducing creative outlets in the library.

|

| Samples of postcards created and ready to be mailed. |

|

| Rutgers University Art Librarian Megan Lotts and BRCC Reference Librarian Peter Klubek demonstrate a completed postcard. |

Maker spaces have been embraced by libraries everywhere and can include anything from 3-D printers, to science experiment stations. The following article from Information Technology & Libraries explains more about how libraries are involved with makerspaces.

Reprinted from: Colegrove, T. (2013). Editorial Board Thoughts: Libraries

as Makerspace?. Information Technology & Libraries, 32(1), 2-5.

Editorial Board Thoughts: Libraries as Makerspace?

Recently there has been tremendous interest in

“makerspace” and its potential in libraries: from middle school and public

libraries to academic and special libraries, the topic seems very much top of

mind. A number of libraries across the country have been actively expanding

makerspace within the physical library and exploring its impact; as head of one

such library, I can report that reactions to the associated changes have been

quite polarized. Those from the supported membership of the library have been

uniformly positive, with new and established users as well as principal donors

immediately recognizing and embracing its potential to enhance learning and

catalyze innovation; interestingly, the minority of individuals that recoil at

the idea have been either long-term librarians or library staff members.

I suspect the polarization may be more a function of

confusion over what makerspace actually is. This piece offers a brief overview

of the landscape of makerspace—a glimpse into how its practice can dramatically

enhance traditional library offerings, revitalizing the library as a center of

learning.

Been Happening for Thousands of Years . . .

Dale Dougherty, founder of MAKE magazine and Maker Faire,

at the “Maker Monday” event of the 2013 American Library Association Midwinter

Meeting framed the question simply, “whether making belongs in libraries or whether

libraries can contribute to making.” More than one audience member may have

been surprised when he continued, “It’s already been happening for hundreds of

years—maybe thousands.”1

“The O’Reilly/DARPA Makerspace

Playbook describes the overall goals and concept of makerspace (emphasis

added): “By helping schools and communities everywhere establish Makerspaces,

we expect to build your Makerspace users' literacy in design, science,

technology, engineering, art, and math. . . . We see making as a gateway to

deeper engagement in science and engineering but also art and design.

Makerspaces share some aspects of the shop class, home economics class, the art

studio and science lab. In effect, a Makerspace is a physical mashup of these

different places that allows projects to integrate these different kinds of

skills.”2

Building users’ literacies across multiple domains and a

gateway to deeper engagement? Surely these are core values of the library; one

might even suspect that to some degree libraries have long been makerspace. A

familiar example of maker activity in libraries might include digital media:

still/video photography and audio mastering and remixing. YOUmedia network,

funded by the Macarthur Institute through the Institute of Museum and Library

Services, is a recent example of such effort aimed at creating transformative

spaces; engaged in exploring, expressing, and creating with digital media,

youth are encouraged to “hang out, mess around, and geek out.” A more

pedestrian example is found in the support of users with first-time learning or

refreshing of computer programming skills. As recently as the 1980s, the

singular option the library had was to maintain a collection of print texts.

Through the 1990s and into the early 2000s, that support improved dramatically

as publishers distributed code examples and ancillary documents on accompanying

CD or DVD media, saving the reader the effort of manually typing in code

examples. The associated collections grew rapidly, even as the overhead

associated with the maintenance and weeding of a collection that was more and

more rapidly obsoleted grew more. Today, e-book versions combined with ready

availability of computer workstations within the library, and the rapidly

growing availability of web-based tutorials and support communities, render a

potent combination that customers of the library can use to quickly acquire the

ability to create or “make” custom applications.

With the migration of the supporting print collections

online, the library can contemplate further support in the physical spaces

opened up. Open working areas and whiteboard walls can further amplify the

collaborative nature of such making; the library might even consider adding

popular hardware development platforms to its collection of lendable

technology, enabling those interested to check out a development kit rather

than purchase on their own. After all, in a very real sense that is what

libraries do—and have done, for thousands of years: buy sometimes expensive

technology tailored to the needs and interest of the local community and make

it available on a shared basis.

Makerspace: a continuum

Along with outreach opportunities, the exploration of how

such examples can be extended to encompass more of the interests supported by

the library is the essence of the maker movement in libraries. Makerspace

encompasses a continuum of activity that includes “co-working,” “hackerspace,”

and “fab lab”; the common thread running through each is a focus on making

rather than merely consuming. It is important to note that although the terms

are often incorrectly used as if they were synonymous, in practice they are

very different: for example, a fab lab is about fabrication. Realized, it is a

workshop designed around personal manufacture of physical items— typically

equipped with computer controlled equipment such as laser cutters, multiple

axis Computer Numerical Controlled (CNC) milling machines, and 3D printers. In

contrast, a “hackerspace” is more focused on computers and technology,

attracting computer programmers and web designers, although interests begin to

overlap significantly with the fab lab for those interested in robotics.

Co-working space is a natural evolution for participants of the hackerspace; a

shared working environment offering much of the benefit of the social and collaborative

aspects of the informal hackerspace, while maintaining a focus on work. As

opposed to the hobbyist that might be attracted to a hackerspace, co-working

space attracts independent contractors and professionals that may work from

home.

It is important to note that it is entirely possible for

a single makerspace to house all three subtypes and be part hackerspace, fab

lab, and co-working space. Can it be a library at the same time? To some

extent, these activities are likely already ongoing within your library, albeit

informally; by recognizing and embracing the passions driving those

participating in the activity, the library can become central to the greater

community of practice. Serving the community’s needs more directly,

opportunities for outreach will multiply even as it enables the library to

develop a laser-sharp focus on the needs of that community. Depending on

constraints and the community of support, the library may also be well-served by

forming collaborative ties with other local makerspace; having local partners

can dramatically improve the options available to the library in day-to-day

practice, and better inform the library as it takes well-chosen incremental

steps. With hackerspace/co-working/fab lab resources aligned with the

traditional resources of the library, engagement with one can lead naturally to

the other in an explosion of innovation and creativity.

Renaissance

In addition to supporting the work of the solitary

reader, “today's libraries are incubators, collaboratories, the modern

equivalent of the seventeenth-century coffeehouse: part information market,

part knowledge warehouse, with some workshop thrown in for good measure.”3

Consider some of the transformative synergies that are already being realized

in libraries experimenting with makerspace across the country:

• A child reading about robots able

to go hands-on with robotics toolkits, even borrowing the kit for an extended

period of time along with the book that piqued the interest; surely such access

enables the child to develop a powerful sense of agency from early childhood,

including a perception of self as being productive and much more than a

consumer.

• Students or researchers trying to

understand or make sense of a chemical model or novel protein strand able not

only to visualize and manipulate the subject on a two-dimensional screen, but

to relatively quickly print a real-world model to be able and tangibly explore

the subject from all angles.

• Individuals synthesizing

knowledge across disciplinary boundaries able to interact with members of

communities of practice in a non-threatening environment; learning, developing,

and testing ideas—developing rapid prototypes in software or physical media,

with a librarian at the ready to assist with resources and dispense advice

regarding intellectual property opportunities or concerns.

The American Libraries

Association estimates that as of this printing there are approximately 121,169

libraries of all kinds in the United States today; if even a small percentage

recognize and begin to realize the full impact that makerspace in the library

can have, the future looks bright indeed. EDITORIAL BOARD THOUGHTS: LIBRARIES

AS MAKERSPACE? | COLEGROVE 5

REFERENCES 1. Dale Dougherty, “The New Stacks: The Maker

Movement Comes to Libraries” (presentation at the Midwinter Meeting of the

American Library Association, Seattle, Washington, January 28, 2013).

http://alamw13.ala.org/node/10004.

2. Michele Hlubinka et al., Makerspace Playbook, December

2012, accessed February 13, 2012, http://makerspace.com/playbook.

3. Alex Soojung-Kim Pang, "If Libraries did not

Exist, It Would be Necessary to Invent Them," Contemplative Computing,

February 6, 2012, http://www.contemplativecomputing.org/2012/02/if-libraries-did-not-exist-it-would-benecessary-to-invent-them.html.

The poetry reading posted last month with Mary Elizabeth Lee was a huge success! Ms. Lee read some of her poems, interacted with our students, and even encouraged them to share their own poetry.

|

| Ms. Lee interacting with students. |

|

| Ms. Lee reading poetry from her book Beveled Edges and Mitered Corners. |

|

| Jeremiah Rogers sharing his poetry with the group. |

|

| Ernest Lee excited to get his book signed by the author. |

|

| Vanessa White with the author. |

"What's my movie?" is a fun little web site that can help you remember the title of a movie. Supply some information about the plot and/or some of the stars and you will receive a list of matching movies. Those of us who have experimented with it in the library have found it to reliably predict the movie you are looking for within the first two movies listed. Try it!