there are many ways for you to get involved, get engaged, and feed that overall sense of curiosity that comes from living and working within an academic environment. And the library is here to help!

Your BRCC librarians have attended a professional development session aimed at improving the collection. Read about what we have learned, and look for these developments in the near future!

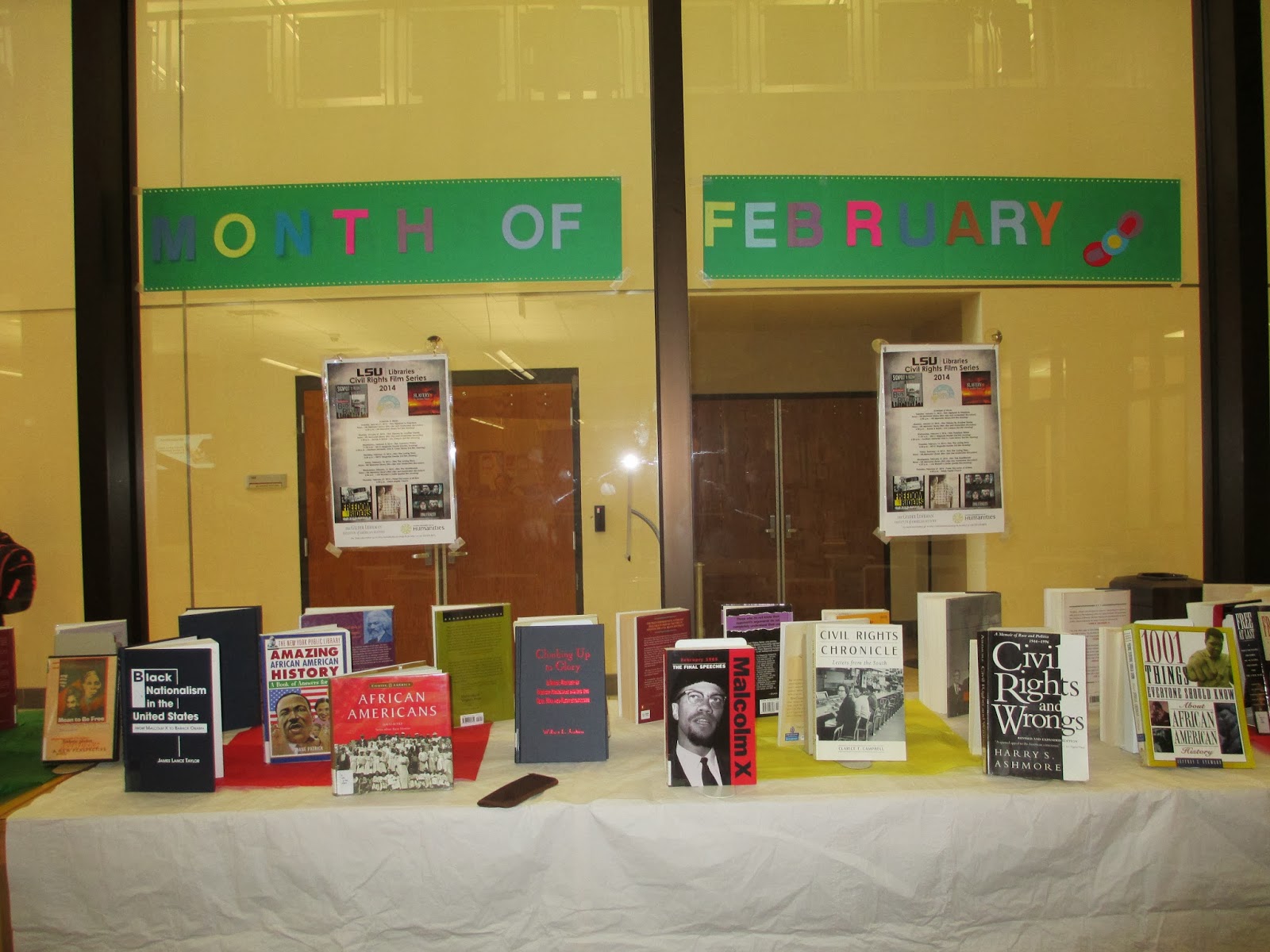

Displays, films, and events in celebration of Black History Month are offered throughout the month. Come participate in one, or all, and learn about the important contributions of African Americans to our history!

The "Resource Spotlight" highlights the eBook collection this month. At the same time, the book club is gearing up for another semester. Preview this month's book club selection using the eBook collection, and find out more about how you can join the club!

Two articles, one on stand up comedians and the delivery of library instruction and another on how to effectively use Wikipedia in libraries, have been reprinted here. Discover how you can incorporate these ideas in your class!

All this and more!

Librarians Professional Development

|

| Dr. Kurz leads the BRCC librarians in a discussion on the Multi-Ccultural Chilrens Collection |

In January, your BRCC librarians participated in a professional development program that focused on the Multi-Cultural-Childrens Collection. The session was led by Dr. Robin Kurz from LSU School of Library and Information Science.

|

| Dr. Kurz, her gaduate student, and Dean Chavis |

Based on her recommendations, the librarians are planning on revising the collection policy for this collection, as well as the relocation of some materials to a general children's collection. These items are kept in the library in support of the Care and Development of Young Children program, a program that has changed significantly with the CATC merger.

Online Learning Student Orientation

Librarian Lauren McAdams spoke at the Online Learning Student Orientation on January 15. The event was hosted by eLearning Program manager Susan Nealy. Students in attendance at the event got tips on how to succeed in online classes and learned about the Magnolia Library's Online Databases, which are available 24/7.

If you would like to schedule a similar session on the library's databases for your class, contact your liaison, call the library (216-8555), or e-mail librarian@mybrcc.edu to find out more.

Monthly Display

|

| February Display featuring Black History Month |

Stop by and visit today!

Civil Rights Film Series

The BRCC Magnolia Library is pleased to announce a collaboration with LSU Libraries, Southern University Library, East Baton Rouge Parish Libraries, and West Baton Rouge Museum in the NEH initiative "Created Equal: America’s Civil Rights Struggle."

As part of this program, we screened two films in February.

Freedom Riders - Wednesday, Feb. 5, 11 a.m., Magnolia Theatre

The Freedom Rides of 1961 were a pivotal moment in the long Civil Rights struggle that redefined America. Based on Raymond Arsenault’s recent book, this documentary film offers an inside look at the brave band of activists who challenged segregation in the Deep South. Produced and directed by Stanley Nelson. Mark Samels, executive producer for American Experience, WGBH.

The Loving Story - Thursday, Feb. 13, 6:30 p.m., Magnolia Theatre

The moving account of Richard and Mildred Loving, who were arrested in 1958 for violating Virginia’s ban on interracial marriage. Their struggle culminated in a landmark Supreme Court decision, Loving v. Virginia (1967) which overturned anti-miscegenation laws in the United States. Directed by Nancy Buirski; produced by Nancy Buirski and Elisabeth Haviland James. A co-production of Augusta Films and HBO Films. Distributed by Icarus Films.

Come and join the Magnolia Library Book Club! This fun and exciting club is open to all BRCC faculty, staff and students. We meet once per month on Wednesday at 12:15 in the library third floor conference room. This month we will be reading Middlemarch by George Eliot, a classic of English literature. Fans of "Downton Abbey" may find much to interest them in Middlemarch.

Kathy Seidel has been listening to an excellent audio recording of Middlemarch read by Juliet Stevenson. A review of this audiobook can be found here.

In addition, there was an interesting review on NPR last month of a new book that gives us glimpses into Middlemarch, and may tempt you to read the classic along with us. Look for that here.

Middlemarch is available in the Magnolia Library with call number PR4662 .A2 ELI 1994. It is also available electronically in our eBook Collection and through Project Gutenberg.

Our next meeting will be on Wednesday, March 26, at 12:15. For more information about the Magnolia Library Book Club, please contact Kathy Seidel at seidelk@mybrcc.edu. Happy Reading!

What stand-up comedians teach us about library instruction

Four lessons for the classroom

Reprinted from College and Research Libraries news January 2014 75 (1)

+ Author Affiliations

Imagine a typical stand-up comedian speaking to audiences from a stage in a dark comedy club, holding a microphone and leaning on a stool, perhaps making observations about airline food. Now picture a typical instruction librarian in a classroom, presenting resources and evaluation strategies to students, perhaps making observations about scholarly communication.

At first glance, the two appear to have little in common. After watching stand-up comedians perform in a wide variety of venues, I have found that there are not only more similarities than one might expect, but several compelling lessons that librarians can learn from comedians and apply to their own instruction to lead more dynamic classes.

Stand-up comedy has seen a renaissance in recent years due to a burgeoning number of creative alternative comedians and the prevalence of tools such as Twitter and YouTube that make access to comics effortless.

Comedians present their jokes, or “material,” in settings ranging from neighborhood bars to stadiums, and perform anywhere between ten minutes and one hour. Given comedians’ extensive experience in public speaking, engaging audiences, and performing for new faces night after night, it is only sensible that some rules and techniques for stand-up can be used to deliver quality library instruction.

From the beginning of an instruction session to its conclusion, below are four lessons librarians can learn from seasoned stand-ups.

Know how to read an audience

Every reference librarian has led a class that, for whatever reason, did not go as well as anticipated. The comedy world has a dramatic term for unappreciated performances. Bombing—telling jokes and receiving no laughs from the audience—is the worst possible outcome for a comedian. Although even a great comic has an occasional off-night, bombing is frequently the result of miscommunicating with a crowd.

The key to preventing bombing is to assess an audience’s expectations on the fly. Comedians, like library instructors, know to vary their material according to the crowd. The jokes that tourists enjoy may be met with blank, uninterested stares by locals in the same way that graduate students are likely to react to being taught freshmen-level research concepts.

Many comedians use crowd work to begin their performance, which involves calling on an audience member, asking him or her a simple question such as, “Where are you from?” or “What do you do?” and quickly finding a response that the crowd will laugh at. This engages the audience and gives the comic an immediate feel for what types of jokes they find humorous.

Eddie Murphy, an immensely popular comedy veteran who made the transition from stand-up to famous actor, skillfully improvises with a large crowd during his classic 1983 cable special Delirious.1 Murphy not only seizes natural breaks in his performance as an opportunity to acknowledge his audience and take a moment’s rest, but he devises quick retorts to hecklers’ remarks, which wins the crowd’s complete attention.

Applying these principles to library instruction, try commencing class with an icebreaker or a short humorous anecdote. If the group is responsive, ask someone to share a “something-that-happened-to-me” story about an experience in a library. A little crowd work as you begin a session can help students connect with each other and yourself, while setting the tone for the class.

Vary your teaching methods

Librarians providing instruction understand that their teaching methods should go beyond a traditional lecture. What may not be apparent is just how many pedagogical approaches are at one’s disposal. In an entertainment industry where standing on a stage and speaking is de rigeur, the cerebral comic Demetri Martin has successfully incorporated props, visual aids, and music into his work. Take Martin’s 2012 comedy special Standup Comedian as an example. In the space of one hour, only ten minutes longer than the typical one-shot instruction session, Martin captivates audiences with his easel pad for humorous drawings and charts, examples of fake flyers he posted at coffee shops, and by playing guitar and harmonica while telling jokes.

Thankfully, instruction librarians are not expected to play multiple instruments while teaching classes, much less deliver jokes. Taking a closer look at Martin’s methods, he explains the logic behind using an easel pad to convey ideas during his performance in Standup Comedian:

Sometimes when I do jokes they don’t work the way I intended, they don’t work as well as I wanted them to, and it’s frustrating, but I hate to give up on a joke...these are some of my jokes that didn’t work the first time around, but I think it’s because I didn’t convey the picture that was in my head, the visual that I was trying to communicate to the audience. But I think that with these “material enhancers” they might work.2

Different teaching methods will be appropriate for different messages. A task that students often find challenging, such as selecting pertinent keywords for searches, could be made easier and more fun by drawing concept maps on an easel pad a la Martin’s approach. Depending on your objectives you may choose to integrate clickers, an interactive game, or a chalkboard into instruction sessions, but Martin demonstrates that the key is to use a variety of methods to reach the audience’s diverse learning styles and keep them involved.

Relate on a personal level

Building empathy and relating with students on a personal level is an effective means of decreasing barriers and the library anxiety of those who may see librarians as unapproachable. All good comedians understand the importance of relatability and incorporating individual experiences into their acts, but perhaps none more so than Louis C.K. As a divorced father of two attempting to balance his longtime comedy career with being a single parent, many of C.K.’s jokes are based on his personal life.

In his critically acclaimed television show Louie, C.K. touches on the same subjects as in his stand-up, from living in New York City (“I like New York. This is the only city where you actually have to say things like, ‘Hey, that’s mine. Don’t pee on that.’”) to divorce (“Being single at 41 after ten years of marriage and two kids is difficult. That’s like having a bunch of money in the currency of a country that doesn’t exist anymore.”)

The best way to create relatability is to teach as your authentic self. If you do not consider yourself a naturally funny person, there is no need to laboriously work jokes into your instruction routine. Instead, try smiling and being natural, and be conversational if the session calls for it. In both the comedy club and the classroom, a dash of personality and spontaneity will improve your performance, and has the added benefit of making you more approachable afterwards.

Use feedback to hone your performance

It is not unheard of for superstar Aziz Ansari of the TV series Parks and Recreation to make surprise guest appearances at small comedy clubs in New York City and Los Angeles. Lucky audience members will see Ansari walk onstage, take his iPhone out of his pocket, press “record,” and set the phone on a stool next to him. After approximately ten minutes of testing new jokes, he will thank the audience and leave to go try his material at another club. Well-known comics will visit up to four shows in one night, recording reactions to their jokes at each appearance. Later they listen to what got big laughs, and what did not, to fine-tune their performances.

Librarians must assess their instruction for the same reason that Ansari records his impromptu performances: to get feedback. Whether asking students questions regarding comprehension using Poll Everywhere, suggesting to a colleague that he or she attend a session to offer advice, or concluding class by having students complete a One-Minute Paper, it is essential to solicit feedback frequently and from a variety of sources. No successful comedian would attempt to spice up a punch line by delivering the identical joke every night without gauging each audience’s reaction. In this same way, instruction should be modified according to the reaction of students, faculty, and colleagues to improve delivery and, consequently, maximize learning opportunities.

Try it again

After receiving feedback on your performance, rework your material and try it again with a new audience. Joan Rivers, a comedian and entertainer for more than 50 years, understands the importance of persistence. The 2010 documentary Joan Rivers: A Piece of Work portrays the comedian’s continual struggle of making people laugh despite in-the-moment challenges she would never have anticipated. In one interview Rivers claims, “The worst thing that ever happened to me on stage is someone ran forward to tell me they loved me and projectile vomited all over the stage.”3 That scenario would certainly make for an instruction session one would rather forget, but the lesson of perseverance in the face of unexpected obstacles speaks for itself.

In the classroom there will invariably be good and bad days, and as instructors it is essential to keep our daily work in perspective. Some sessions may indeed bomb, and when they do, the most productive reaction is to listen to audience expectations, adjust one’s approach, and try again the next day. As any comedian at his or her first open mic can tell you, doing untested material is an arduous undertaking. Remember that no act is perfect the first time. When testing, redesigning, and retesting new material in the classroom, persistence will eventually pay dividends.

Conclusion

Comedians are experts in effectively reading an audience, diversifying their presentation methods, relating to people on a personal level, and tirelessly reworking their material. The next time you watch a comedian pay attention to more than the punch lines. You will find that the methods underpinning the performance apply directly to providing better library instruction and can be easily adopted. Whatever path you take to improve your teaching based on the tried and true methods of stand-ups, please do everyone a favor and refrain from beginning your next class with, “I just flew in from the third floor stacks, and boy are my arms tired!”

- © 2014 Eamon C. Tewell

Using Wikipedia in information literacy instruction

Tips for developing research skills

Reprinted from College and Research Libraries news January 2014 75 (1)

+ Author Affiliations

As an information literacy instructor at Auburn University, it has been a perpetual struggle to teach students how to successfully search for library resources when they come to their one-time library sessions with only a broad paper topic and no idea how to narrow it down. A student recently told me regarding an English composition due in a few days, “The topic is so broad, I can’t pick an argument. I don’t even know where to start.” I began encouraging students to use a resource that they feel comfortable with as a starting point—Wikipedia.

Wikipedia, the online encyclopedia anyone can edit, was founded in 2001. Controversy over its accuracy and validity began then and continues today. Academic departments have banned it, professors and librarians disparage it. However, Wikipedia is going strong, increasing in both users and number of entries each day.1 Although every student in my class raised his or her hand when asked if they used Wikipedia for research, I still received the comment, “I thought Wikipedia was not okay for research at all!” Students continue to use it even though they know it is not a valid source.

However, students feel comfortable using Wikipedia, and they aren’t the only ones. As Debbie Abilock said in a 2012 article, “Our students may acknowledge that Wikipedia is unreliable, but they use it anyway—and so do we.”2 Rather than shunning the site, its popularity can be used as a learning tool. In my classes I have successfully used Wikipedia for topic development and for finding keywords and additional sources. Students may be surprised that it’s “allowed,” but they have embraced the familiar tool and are using it effectively.

Topic development

“Just getting started on a research assignment is the most difficult part of the research process for me.”3 This was a common finding in a survey by Project Information Literacy, and I often hear it in the classroom, as well. Wikipedia is an excellent starting point for students who aren’t sure how to narrow down a broad topic. Professors often give students a choice of larger topics with the expectation that they will select an aspect of one of the topics on which to focus their paper. However, when student are first trying to locate resources, their search strategies reveal they aren’t sure how to make a broad topic into a smaller, manageable thesis statement or research question to which they can respond within a few pages.

For example, sustainability is a theme that appears in English composition courses. The term sustainability applies to a variety of disciplines, and any number of paper topics could emerge from sustainability as a broad topic. This is an opportunity for Wikipedia to be useful. The Wikipedia entry for sustainability offers the subheadings of “environment,” “economy,” and “social issues.”4 Beneath each of those are narrower topics such as “land use,” “economic opportunity,” and “poverty.”

This breakdown, written in easy-to-understand, nonacademic language, allows students to consider their options for a research question, learn a little more about their individual topics, and even offers links to government websites and peer-reviewed journals. Encouraging use of Wikipedia to understand and develop a topic allows students access to this familiar resource while showing them how to use it appropriately.

Identifying keywords

Even if they have some knowledge of their topic, students may struggle with generating keywords for a search strategy in a library database. As an information literacy objective, students should be able to extract relevant keywords from their research topic. For example, “The effect of drilling for oil in Alaska” could yield “oil,” “drilling,” and “Alaska.” In learning to broaden a search strategy students are encouraged to find related terms and phrases. Using a traditional thesaurus will provide alternative terms, but they may not be relevant to the research topic.

A look at the Wikipedia article “Arctic Refuge drilling controversy” provides a number of options for building a search strategy.5 “Oil and drilling and Alaska” becomes “(oil or crude) and (drilling or oil exploration) and (Alaska or ANWR).” Referencing a Wikipedia article to develop a search strategy is a convenient and fast way to find related terms students may have struggled to brainstorm on their own.

Finding additional resources

A third use for Wikipedia articles relevant to a research topic is found in the list of references appearing at the end of every entry. These links offer a valuable opportunity to teach students about bibliography mining, looking at the bibliographies of articles to “mine” additional resources of value. In Wikipedia, these references appear in linked format. Many citations in a Wikipedia article go to other websites, but some reference lists include magazine, newspaper, and journal articles not freely available on the web. This is a chance to show students how to locate and use a variety of sources using both the Internet and library databases. Students can link to another website and consider its validity, or learn to extract the relevant information from a journal citation needed to locate it. Wikipedian editors look at the references as well as the content, and these references are expected to be valid and reliable. One can see from looking at the edit history of any number of Wikipedia entries that they will be removed if they do not meet these criteria.

Conclusion

If information literacy instructors make a commitment to use Wikipedia in the classroom, students have a comfortable platform in which they can begin to learn more reliable means of research. Wikipedia can act as a bridge to help them become familiar with library resources and a new way to research they may have never learned in high school. Wikipedia continues to increase in popularity, and it is likely that students will continue to use it. Scholars, educators, and librarians should not shun it, but rather embrace it and make it work within a structure of information literacy while furthering students’ education.

- © 2014 Cate Calhoun

Notes

This month we are featuring our eBook collection. The eBook collection is offered through EBSCO, does not require an e-reading device (Kindle, Nook, iPad etc.), and is available to you 24/7. With EBSCO's extensive collection of eBook titles, users can search within a wide range of relevant eBooks using the powerful EBSCOhost search experience. With every search, relevant eBook titles will appear directly alongside databases and other digital content, exposing users to the full depth of the library's offerings. Users can access the full text of eBooks from their computer.

Please view the following tutorial to find out more about searching the EBSCO eBook collection.

No comments:

Post a Comment